Statement:

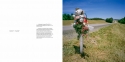

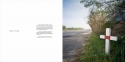

You have seen them while driving on interstates and two lane country roads: weathered stuffed animals, bits of lace or flowers tied to the post of a road sign, or small crosses turned silver gray by the sun. Some have names, dates of birth and death, faded notes, pinwheels, deflated balloons, or other memorabilia.

For the passerby, it is impossible to observe the marker without envisioning the incident or imagining the lives of the survivors. What tragedy occurred? Who built the structure? Does the person who built it live in the area, drive by, and occasionally stop to tend it?

The practice of roadside memorials in the United States is believed to have come from the Southwest, brought by colonists from Spain in the 1700’s. These colonists attached a spiritual significance to the place where the spirit leaves the body, so they built crosses beside the trail to mark the exact spot where a death occurred. Similar crosses are common in other Roman Catholic countries of Europe and in Latin America, where they are called “Descansos,” or resting places. These small makeshift shrines are constructed at the places where the pallbearers rest while carrying the deceased to the graveyard.

Today the US Department of Transportation estimates that there are tens of thousands of roadside memorials and that this number is growing. Some researchers link this recent resurgence to high profile memorials such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the site of the Oklahoma City Bombing, Columbine High School, and the Princess Diana memorial.

In most states these improvised memorials are illegal but generally, out of respect for the deceased and their loved ones, road crews do not disturb them unless they interfere with the flow of traffic. The bereaved build these structures for a number of reasons: as a way to reach out from their private pain in order to connect to a larger support group; as a warning to others not to speed or drive under the influence of alcohol; to let drivers know that someone died there and they were important to someone; or to give a point of reference to a tragic moment. These memorials serve a function that traditional funerals and cemeteries cannot – they honor the deceased and mark the accident that killed them, and offer a more personal way for the bereaved to connect with the person who is now gone.

These memorials are strangely poignant and haunting. They speak of loss and a life abruptly ended. Each structure is intriguing, both as a folk art form and as a spectacle – one can almost imagine the accident and feel the suffering of the survivors. They are transient, most not lasting more than ten years and they remind us briefly that the spirit of someone left their body at this spot.